Today in Literary History: Jan. 30-Feb. 2

Barbara W. Tuchman, Norman Mailer, Langston Hughes, 'Ulysses' is published

Here are your Today in Literary History stories from Bidwell Hollow for Jan. 30-Feb. 2.

Only two more complimentary issues of Today in Literary History remain. These twice-weekly articles become available only to paid subscribers starting on Feb. 10.

You can subscribe below for either $5/month or $50/year. That’s $50 for 104 stories a year (48 cents per story). Your credit card won’t be charged until Feb. 10. Also, all paid subscribers are eligible to win the monthly book giveaway.

Free editions of Today in Literary History left: 2

Jan. 30

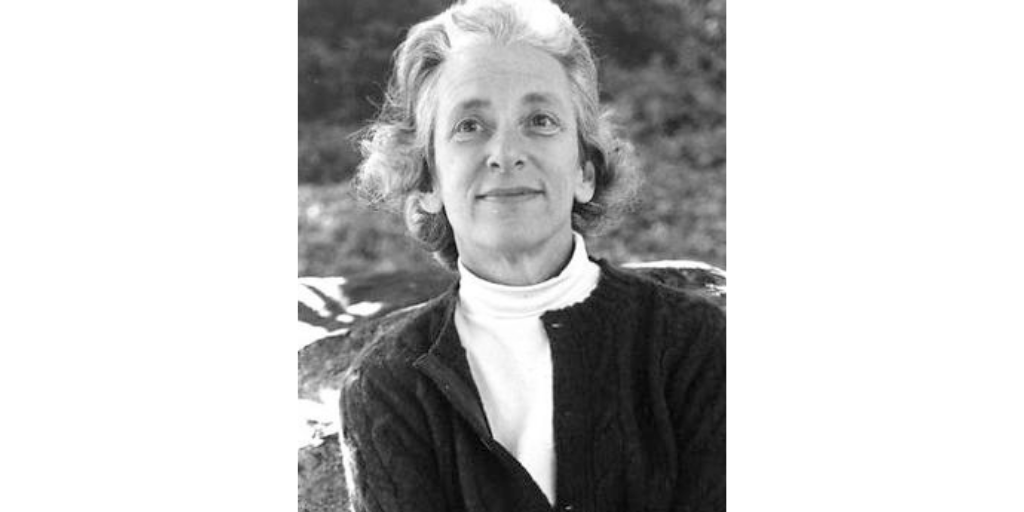

Barbara W. Tuchman

When her three daughters were young, Barbara Tuchman spent her mornings working. Tuchman lengthened her workday once all the kids were old enough for school. And in 1956, she published Bible and Sword; England and Palestine from the Bronze Age to Balfour. It’s a nonfiction book about British involvement in Palestine.

Tuchman admitted she couldn’t have finished Bible and Sword without having domestic help. Still, she lamented the plight of a female amateur historian. “If a man is a writer, everybody tiptoes around past the locked door of the breadwinner. But if you’re an ordinary female housewife, people say, ‘This is just something Barbara wanted to do; it’s not professional.’”

Tuchman didn’t need to write. She was born on Jan. 30, 1912, in New York City to wealthy parents. Her father was a banker who owned The Nation magazine in the 1930s. Her mother was the granddaughter of a U.S. diplomat. And Tuchman’s uncle served as Treasury Secretary under President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

But Tuchman was passionate about history and storytelling. After Bible and Sword, Tuchman published The Zimmermann Telegram and, in 1962, The Guns of August. The latter book focuses on the start of World War I. For it, Tuchman earned her first Pulitzer Prize. Her second Pulitzer came in 1972 for a book about Gen. Joseph Stilwell. He was the American commander in China during World War II.

Tuchman produced historical books despite not having an advanced degree. She graduated from Radcliffe College with a bachelor’s in 1933, but from then on was self-educated. The historian viewed her lack of a Ph.D. as a good thing. “It’s what saved me,” she Tuchman said. “If I had taken a doctoral degree, it would have stifled any writing capacity.”

It’s her focus on storytelling that sets Tuchman’s books apart from many other nonfiction works. Professional historians criticized her writing, but readers loved what Tuchman published. Many of her books became bestsellers, including her last. The First Salute, about the American Revolutionary War, was a New York Times bestseller for at least 17 weeks. It was ninth on the list the week before Tuchman passed away on Feb. 6, 1989, in Greenwich, Conn.

Jan. 31

Norman Mailer

Jan. 31 is the birthday of a writer who won two Pulitzer Prizes but also stabbed his wife. Norman Mailer was born in Long Branch, N.J., in 1923. His family moved to Brooklyn when he was nine, and it’s there he graduated high school at 16.

Mailer headed to Harvard University, where he started writing at least 3,000 words a day. He became editor of the literary magazine The Harvard Advocate. And he won a fiction prize from Story magazine when he was a junior.

But Mailer graduated in the middle of World War II. The U.S. Army drafted and sent him to the South Pacific, an experience which he tapped in writing his first novel. It took Mailer about 15 months to write The Naked and the Dead.

The book came out to rave reviews in 1948. The Naked and the Dead sold 200,000 copies within three months, making Mailer a celebrity. About his newfound fame, the author wrote, “My farewell to an average man’s experience was too abrupt; never again would I know, in the dreary way one usually knows such things, what it was like to work at a dull job, or take orders from a man one hated.”

Mailer spent much of the 1950s writing and also abusing alcohol and drugs. In Nov. 1960, he stabbed his second wife, Adele Morales, in the abdomen and back with a penknife. The attack happened in the early morning hours of Nov. 20 after an all-night party in the couple’s apartment. The police arrested and then released Mailer because Morales declined to press charges. She and the author divorced in 1962.

Mailer went on to marry four more times, for a total of six wives and nine children. It took a lot of money to support that many kids. So starting in the 1960s, Mailer accepted writing assignments for Esquire magazine. Applying literary techniques to his articles, Mailer deployed a style called “new journalism.” It’s a method also used by other writers, such as Joan Didion and Tom Wolfe.

Mailer published 39 books, 11 of which were novels. He won a Pulitzer Prize in 1969 for The Armies of the Night and his second one in 1980 for The Executioner’s Song. His poems appeared in The New Yorker, and he helped found The Village Voice newspaper. But it’s worth noting the author spent many years demeaning women. He once called them “obedient little b——.”

For the last 25 years or so of his life, though, Norman Mailer calmed down. His editor, Jason Epstein, said, “There are two sides to Norman Mailer, and the good side has won.”

Feb.1

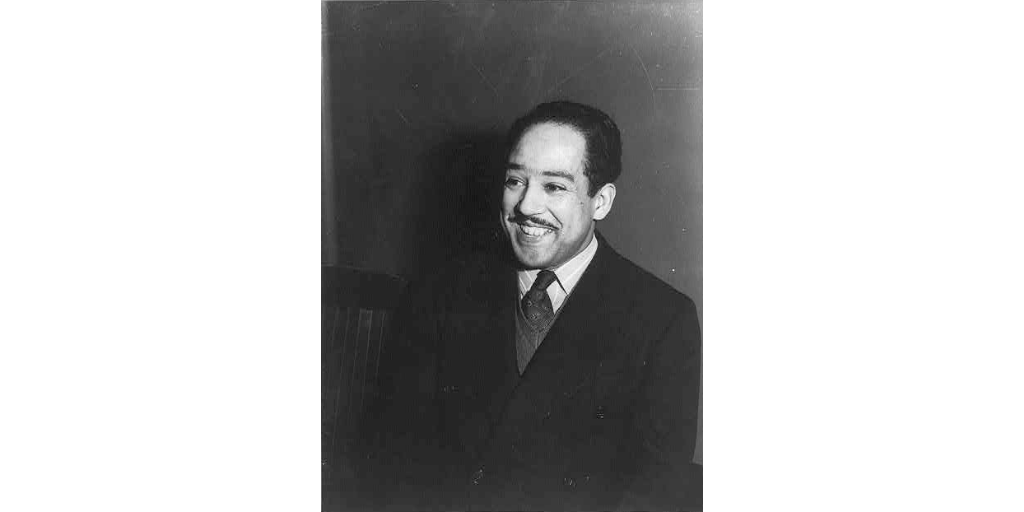

Langston Hughes

The June 23, 1926, issue of The Nation magazine carried an essay by Langston Hughes. In the article, “The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain,” Hughes laments a fellow writer saying he wanted others to know him as “‘a poet—not a Negro poet.’” To Hughes, this means his peer wants to be white. Hughes takes issue with that sentiment.

In his essay, Hughes argues for African American artists embracing their identity. He concludes the piece by saying, “We younger Negro artists who create now intend to express our individual dark-skinned selves without fear or shame. If white people are pleased we are glad. If they are not, it doesn’t matter. We know we are beautiful. And ugly too. The tom-tom cries and the tom-tom laughs. If colored people are pleased we are glad. If they are not, their displeasure doesn’t matter either. We build our temples for tomorrow, strong as we know how, and we stand on top of the mountain, free within ourselves.”

Hughes’s essay expressed the spirit fueling the Harlem Renaissance. Black art and culture took off during this period in early 20th century New York, with Hughes in the middle of it. His first poetry collection, The Weary Blues, came out the same year his essay appeared in The Nation. And his friends included black artists such as James Weldon Johnson and Zora Neale Hurston.

It’s with Hurston that Hughes wrote a play in 1931. Titled “Mule Bone: A Comedy of Negro Life in Three Acts,” the work showcased the Southern black dialect. “It portrays what black people say and think and feel -- when no white people are around,” Dr. Henry Louis Gates Jr. wrote about “Mule Bone.”

While collaborating on “Mule Bone,” though, Hughes and Hurston’s friendship fell apart. The play went unpublished and unproduced until Gates discovered it in 1984. And on Feb. 14, 1991, “Mule Bone” opened at the Ethel Barrymore Theatre in New York.

Hughes’s body of work consists of many poems, essays, and books. He wrote plays, published 11 novels and story collections, at least 16 poetry volumes, and edited many anthologies. And Hughes loved and promoted jazz music. In his 1926 Nation essay, the writer called jazz “one of the inherent expressions of Negro life in America.”

Langston Hughes was born on Feb. 1, 1902, in Joplin, Mo. He grew up in Kansas, Illinois, and Cleveland. After a stint living in Washington, D.C., Hughes arrived in Harlem in New York City in the mid-1920s. He stayed there for the rest of his life, passing away in 1967.

Feb. 2

Ulysses is Published

On Feb. 2, 1922, Sylvia Beach’s Paris bookstore, Shakespeare and Company, published James Joyce’s Ulysses for the first time. New York City-based magazine, The Little Review, first serialized Ulysses between 1918 and 1920. But then New York City convicted the periodical’s editors, Margaret Anderson and Jane Heap, of obscenity for distributing Joyce’s work. The city fined Anderson and Heap $50 each. And they destroyed copies of The Little Review containing Ulysses.

Then Ezra Pound introduced Sylvia Beach to Ulysses. The bookshop owner published 1,000 copies of the novel, 100 of which Joyce autographed. Ernest Hemingway, Gertrude Stein, and William Butler Yeats were some of the first customers to buy the book. The first edition sold out within a month.

People smuggled copies of Ulysses into the U.S. and England. But it wasn’t until 1932 that an American publisher decided to take a chance on releasing the novel. That year Random House President Bennett Cerf came up with a plan. His company would import a copy of the Paris edition of Ulysses. He figured U.S. officials would seize the book, and there would be another obscenity trial.

So Cerf arranged for a copy of Ulysses to arrive in New York in May 1932. Sure enough, U.S. Customs confiscated the book for being obscene. A trial took place and on Dec. 6, 1933, U.S. District Judge John M. Woolsey declared that Ulysses was not obscene. The New York Circuit Court of Appeals upheld Woolsey’s decision in 1934. Shortly after that, on Jan. 25, 1934, the first U.S. edition of Ulysses came out.

Ulysses tells the story of how character Leopold Bloom spends June 16, 1904, in Dublin. Today many regard the book as the most significant novel of the 20th century. And people around the world celebrate June 16 as Bloomsday, a celebration of James Joyce’s life and work. And Feb. 2, by the way, is James Joyce’s birthday.

Sources

Significant effort goes into ensuring the information shared in Bidwell Hollow’s Today in Literary History is factual and accurate. However, errors can occur. If you see a factual error, please let me know by emailing nick@bidwellhollow.com. I'll make every effort to verify and correct any factual inaccuracies. Thank you.

Barbara W. Tuchman

"Barbara Tuchman Dead at 77; A Pulitzer-Winning Historian." Eric Pace. The New York Times. Feb. 7, 1989. Accessed on Jan. 28, 2020.

"Barbara Tuchman." The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. Encyclopaedia Britannica. Jan. 26, 2020. Accessed on Jan. 28, 2020.

"Barbara W. Tuchman." Oliver B. Pollak. The Encyclopedia of Jewish Women. Accessed on Jan. 28, 2020.

"A Heroine of Popular History." Bruce Cole. The Wall Street Journal. March 10, 2012. Accessed on Jan. 28, 2020.

"Balfour Declaration." The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. Encyclopaedia Britannica. Jan. 8, 2020. Accessed on Jan. 28, 2020.

Norman Mailer

"Norman Mailer, Towering Writer With Matching Ego, Dies at 84." Charles McGrath. The New York Times. Nov. 10, 2007. Accessed on Jan. 29, 2020.

"The Novel that Norman Mailer Didn't Write." Richard Brody. The New Yorker. Oct. 16, 2013. Accessed on Jan. 29, 2020.

"Norman Mailer Arrested in Stabbing of Wife at a Party." The New York Times. Nov. 22, 1960. Accessed on Jan. 29, 2020.

"Norman Mailer Speaks to America From Beyond the Grave." Abby Margulies. Tablet. Oct. 15, 2013. Accessed on Jan. 29, 2020.

"A Brief History of Norman Mailer." J. Michael Lennon. PBS. Oct. 19, 2001. Accessed on Jan. 29, 2020.

"Notes on the New Journalism." Michael J. Arlen. The Atlantic. May 1972. Accessed on Jan. 29, 2020.

"Norman Mailer." Jesse Kornbluth. May 10, 1967. The Harvard Crimson. Accessed on Jan. 29, 2020.

Langston Hughes

"Langston Hughes." Academy of American Poets. Accessed on Jan. 29, 2020.

"Mule Bone." The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. Encyclopaedia Britannica. Nov. 22, 2016. Accessed on Jan. 29, 2020.

"Mule Bone." Internet Broadway Database. Accessed on Jan. 29, 2020.

"Why the 'Mule Bone' Debate Goes On." Henry Louis Gates Jr. The New York Times. Feb. 10, 1991. Accessed on Jan. 29, 2020.

"The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain." Langston Hughes. Poetry Foundation. Accessed on Jan. 29, 2020.

"Revisiting the Racial Mountain." Gregory Pardlo. PEN AMERICA. Feb. 16, 2010. Accessed on Jan. 29, 2020.

"The Elusive Langston Hughes." Hilton Als. The New Yorker. Feb. 16, 2015. Accessed on Jan. 29, 2020.

"Jazz Poetry & Langston Hughes." Rebecca Gross. National Endowment for the Arts. April 11, 2014. Accessed on Jan. 29, 2020.

"Harlem Renaissance." History.com Editors. Oct. 29, 2009. Updated on Jan. 16, 2020. Accessed on Jan. 29, 2020.

Ulysses

"The Little Review 'Ulysses'." James Joyce. Yale University Press. 2015.

"'Ulysses' by James Joyce, Published by Shakespeare and Company." British Library. Accessed on Jan. 29, 2020.

"The Story Behind the First Edition of Ulysses by James Joyce." Rebecca Romney. Bauman Rare Books. July 8, 2013. Accessed on Jan. 29, 2020.

"'Ulysses' and obscenity." David Bradshaw. British Library. May 25, 2016. Accessed on Jan. 29, 2020.

"'Ulysses'." Simon Stern. The First Amendment Encyclopedia. Accessed on Jan. 29, 2020.

"Carving a Literary Exception: The Obscenity Standard and 'Ulysses'." Marisa Anne Pagnattaro. Twentieth Century Literature. Vol. 47, No. 2, Summer, 2001.

"75 Years Since First Authorised American Ulysses!" The James Joyce Center. Nov. 3, 2012. Accessed on Jan. 29, 2020.

"The Romantic True Story Behind James Joyce's Bloomsday." Lily Rothman. Time. June 16, 2015. Accessed on Jan. 29, 2020.