This Week in Literary History: March 8-14

Recognizing the birthdays of Viet Thanh Nguyen, John McPhee, and more

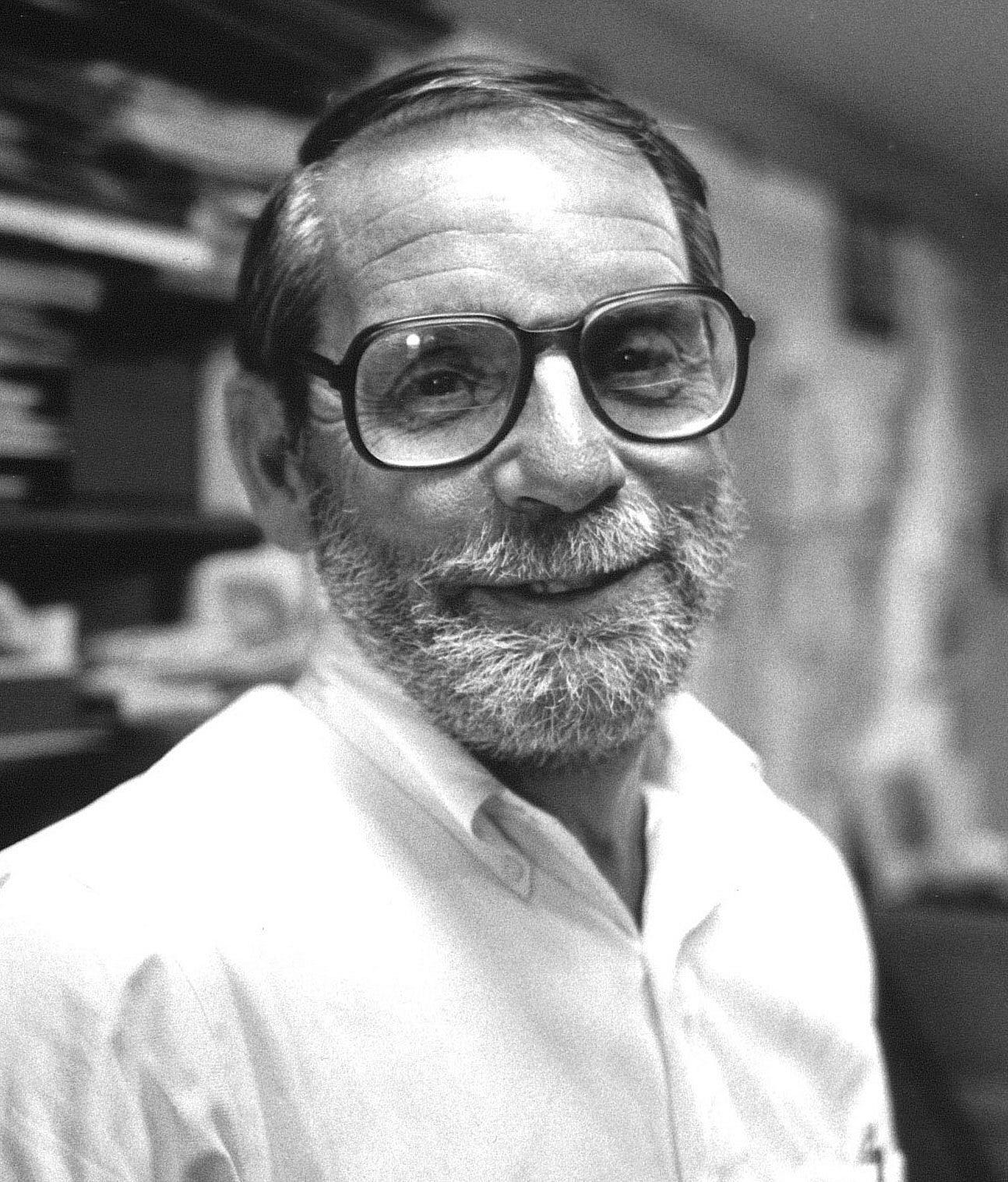

The Shy Depths of John McPhee’s Writing

By Andrew Sanger

There's a poster stapled to the door of John McPhee's office at Princeton University. It's in the style of a medieval-style triptych which depicts souls in the afterlife screaming for mercy as demons torture them in manners both creative and horrific. McPhee has dubbed the poster "A Portrait of the Writer at Work."

As readers engrossed in the pages of a well-polished product, it's easy to forget the painstaking slog which leads up to that final draft. It's a popular myth that genius writing manifests itself as inspired prose that seamlessly flows from its author's pen. The reality, however, could not be more different, and John McPhee is no exception.

McPhee has more than 30 titles to his name, and according to his 2017 book on writing, Draft No. 4, not one of them has come to him easily. The book outlines McPhee's rigorous, obsessive, borderline-masochistic approach to constructing literary nonfiction and is more or less based on his "Creative Nonfiction" course, which he's taught at Princeton for over 40 years.

According to McPhee, his first stumbling block in the writing process is always structure. "I'm obsessed with the structure of pieces of writing," McPhee once said when discussing the massive amounts of time and creative energy he spends plotting the narrative flow of his stories.

These labors' results are diagrams that more resemble mathematical equations or ancient cave paintings than a traditional outline. McPhee likes to call them "doodles." One such example is a nautilus shell spiral which he mysteriously labeled at various points with terms like "turtle," "weasel," and "muskrat." This doodle went on to become his 1973 essay "Travels in Georgia."

Despite the struggle of building out a story's structure, for McPhee, it's also the best way to break through writer's block.

"Nonfiction writers have been out collecting material, and now they're getting ready to write, and they've got a great mound of stuff on a table… Leaning on structural planning is what got me out from under a 50-ton rock that was lying on my chest," explained McPhee in an interview.

McPhee first learned this lesson as a Princeton High School student, just a few minutes' drive from where he now teaches. He remembers how his English teacher, Olive McKee, "couldn't care less what you wrote about, or if it was fact or fiction, but it had to have this little doodle." Now McPhee requires the same of all his students, too.

Since getting his start writing for Time and The New Yorker, John McPhee has made his career by revealing how the seemingly mundane, banal, and often overlooked aspects of life can contain vast worlds in and of themselves. Much of his work focuses on the natural world, a passion he attributes to his early years attending a summer camp in Vermont named Keewaydin.

McPhee's covered the wilderness of New Jersey, the craft behind birch-bark canoes, and the American shad (a species of fish), as well as a plethora of other topics covered in his books and hundreds of published essays. He's the sort of writer who can produce a book simply titled Oranges and captivate his readers with the depths of historiological intrigue surrounding citrus.

In Draft No. 4, McPhee delivers wisdom and observation not only on the writing process but also on writers themselves. While reminiscing about his struggles getting started as a freelancer, McPhee writes that "Writers come in two principal categories—those who are overtly insecure and those who are covertly insecure."

The term "covert" seems appropriate for McPhee, who has never had his photograph appear in any of his published work. McPhee refers to himself as "shy to the point of dread," a point proven by his politely declining to attend an 80th birthday celebration put together by his friends and colleagues.

McPhee, who prefers to be the interviewer rather than the interviewee, considers this shyness one of his writing strengths. In a 2017 interview, McPhee said, "As an interviewer, I don't think I come on very strongly, and I think that's an advantage… I think that in my sort of work a person who perhaps had more confidence might end up with less material, if you see what I'm saying. I mean, if you obviously need help, who's going to help you but the person you're trying to write about?"

Never one to call unnecessary attention to himself, McPhee's writing philosophy works in harmony with his life philosophy: to be the quiet and intent observer of a subject aching to expose its innermost intricacies.

John McPhee

Born on March 8, 1931, in Oban, U.K.

A Children’s Author Who Helped Kids See Themselves in Stories

By Emily Quiles

In elementary school, Virginia Hamilton won prizes for reading the most books over the summer. The Nancy Drew mystery series was a favorite.

"I loved winning prizes," Hamilton said. "The award was usually a beautifully colored book. And those kinds of books were not easy to come by when I was a child!"

Born in Yellow Springs, Ohio, the first story Hamiton remembered hearing was of her grandfather, Levi Perry, a former slave in Virginia, who left for Ohio as an infant via the Underground Railroad. "My mother told me," Hamilton recalled. "I think it had a profound effect on me."

In fact, Hamilton's name comes from the state her grandfather left during his journey to liberation.

"My mother named me Virginia so that I would never forget the history of my own family," Hamilton explained. Her childhood neighborhood also served as a constant reminder. "I grew up in an area that had a lot of houses from the Underground Railroad, so I knew about slavery just by osmosis."

Hamilton's family encouraged her to read and write. "I think I was the one whom everyone thought would be the chronicler," she said. "The one who wrote things down."

Hamilton graduated at the top of her high school class, earning a full scholarship to Antioch College. She transferred to Ohio State University in Columbus in 1956. Then, shortly after receiving a degree in literature and creative writing, Hamilton left for New York City. In New York, she worked as a museum receptionist, cost accountant, and nightclub singer while pursuing a published writer's path.

At the age of 31, Hamilton published her first book for children, Zeely. It's the story of an imaginative American Black girl who, through storytelling, learns to live for herself and not for the stories that she creates about others. Her debut novel paved the way for "Liberation Literature," which seeks to present school students with often under-represented groups. As a Southern Poverty Law Center website, Learning for Justice says, "The use of liberation literature ensures that texts used in the classroom are mirrors for all children."

"It was a 1960s inspiration," Hamilton explained. "I was a '60s person. We were looking to our heritage - our homeland."

"Liberation Literature" is not only about the protagonist's freedom, but also the reader's. "(Hamilton) talked about 'Liberation Literature' as allowing the reader to be a witness to the protagonist's suffering and also the triumph," said Rudine Sims Bishop, Professor Emerita of Education at The Ohio State University.

Hamilton refined her craft for character development through observation. "I do a lot of people watching," she said. "At a very early age, I realized that what people were talking about may not be seen in the expression on their faces. I learned that what you say is not necessarily what you mean, by watching your body language."

"A poet once wrote 'I think what I see.' And that's what happens," Hamilton said. "I see them in my head, I see them come to life, and I like to describe what I see very clearly. The way they move and the expressions on their faces define them. They have to come to life for me first before they can come to life for anybody else."

Over her short life of 65 years, Hamilton published over 40 children's books, including Dies Drear, where she told her grandfather's stories. Respected for her themes of memory, tradition, and generational legacies as they influence African Americans' lives, Hamilton won every major award in youth literature. She received the U.S. National Book Award for children's books and was the first Black author to receive the Newbery Medal.

"She wasn't just talking about a runaway slave who found his freedom," her husband, Arnold Adoff, told Open Road Media. "She was talking about the way people deal with each other and view the human experience."

Virginia Hamilton

Born on March 12, 1934, in Yellow Springs, Ohio

Died on Feb. 19, 2002, in Dayton, Ohio

Viet Thanh Nguyen Encourages to Look Beyond for Something Better

By Andria Kennedy

"We need to recognize that, yes, we are human, but we are all capable of both inhuman and human acts. Whether we are part of the imperial project or the natives on which the imperial acts are enacted, none of us are excused from these realities of humanity and inhumanity."

Viet Thanh Nguyen's words are powerful and speak firmly to everyone - American and Vietnamese. They represent the foundation of his non-fiction work, Nothing Ever Dies: Vietnam and the Memory of War. But there's more to it than that. The philosophy speaks toward every war humanity has ever engaged in - and those lying in wait in our future.

Nguyen stands apart from many Vietnamese refugee writers. While acknowledging the importance of speaking for those like him in the United States, he understood from the very beginning that he was confronting a difficult wall.

"Refugee writers, simply by acknowledging that history, introduce some troubling elements into the American story," Nguyen said. "The existence of Vietnamese refugee writers talking about Vietnamese refugees, acknowledging the history of the war in Vietnam, means that the Americans who read these books - or anyone who reads these books - has to at least acknowledge this war took place."

Even in the U.S., opinions over the Vietnam War (or the American War, depending on who you speak to) differ widely. And writing works that call attention to such a controversial conflict? Nguyen knew it was a risk.

But he undertook the challenge. And in 2016, The Sympathizer received the Pulitzer Prize, even with its slant of political satire regarding the Vietnam war.

Viet Thanh Nguyen fully admits to his decision regarding the tone of the novel. "This perspective makes many Americans uncomfortable, but I felt it was important to counter the dominance of the 'well-intentioned American' argument, particularly as a Vietnamese refugee. People like me are not expected to say these things. We're expected to be grateful to the United States for rescuing us, but the novel satirizes that idea by saying, 'We're grateful for being rescued, but maybe we wouldn't have needed it if you hadn't bombed us in the first place.'"

Nguyen speaks in a unique voice that asks people to open their eyes. Not just toward the Vietnamese refugee population, but for all refugees seeking asylum throughout the world. "Wars always produce refugees. Refugees often, not always, come from wars," he states. And he challenges us to rethink our way of looking back on the wars of our past. Too often, we examine one side of a conflict with a critical eye, neglecting to turn the same microscopic view to those we opposed. And in the narrowed view, we lose the chance to gain essential lessons - and get past the conflict.

"I argue that we need an ethics of the inhuman, where it's not simply that we're trying to correct versions of the past to be more inclusive; but, actually, we need to recognize how it is that we're not all human," Nguyen said. "We're also inhuman, and that is actually what drives us to go back to war over and over again."

Nguyen's words speak clearly, but they're difficult to swallow. It requires a willingness to overlook political rhetoric and acknowledge a lack of civilization within ourselves.

Nguyen's a hopeful person, encouraging his readers - whether they choose his fiction or non-fiction - to look beyond the situation to something better. The lessons of the past have more to teach us through pain and suffering than from gentility and white-washing.

Viet Thanh Nguyen's words state things concisely. "If, as a country, we had mechanisms in place to hear from the diverse peoples in our own country, but also the rest of the world, I imagine we'd be less inclined to support these imperial endeavors."

Viet Thanh Nguyen

Born on March 13, 1971, in Buon Ma Thuot, Vietnam

Sources

Significant effort goes into ensuring the information shared in Bidwell Hollow’s content is factual and accurate. However, errors can occur. If you see a factual error, please let me know by emailing nick@bidwellhollow.com. I’ll make every effort to verify and correct any factual inaccuracies. Thank you.

John McPhee

“The Mind of John McPhee.” Sam Anderson. The New York Times. Sep. 28, 2017.

“Assembling the written word: McPhee reveals how the pieces go together.” Jennifer Greenstein Altmann. Princeton University. May 7, 2007.

“John McPhee on Writing and the Relationship Between Artistic Originality and Self-Doubt.” Maria Popova. BrainPickings. July 29, 2020.

“What I think: John McPhee.” Jamie Saxon. Princeton University. Sep. 18, 2017.

Virginia Hamilton

“Biography.” Virginia Hamilton. Virginia Hamilton Official Website.

“Overview Zeely.” Oxford Reference. Accessed on Feb. 23, 2021.

“Virginia Hamilton Interview Transcript.” Scholastic students. Scholastic.

“Virginia Hamilton on Liberation Literature.” Open Road Media. Feb. 3, 2014.

"Virginia Hamilton.” Snipets. Filed Communications. 1980.

“Virginia Hamilton.” Voices from the Gaps. University of Minnesota. 2009.

"Liberation Literature and Counter-narratives." LearningforJustice.org.

Viet Thanh Nguyen

"Unsettling the American Dream: The Millions Interviews Viet Thanh Nguyen." Jianan Qian. The Millions. Oct. 17, 2019.

"Nothing Ever Dies: Viet Thanh Nguyen." Joel Whitney.

"A Conversation with Viet Thanh Nguyen." Jinwoo Chong. The Columbia Journal. Oct. 23, 2020.

"Exploring the Past in Writing: An Interview with Pulitzer-Prize Winning Author Viet Thanh Nguyen." Richard Chachowski. The Signal. Nov. 29, 2020.

"Viet Thanh Nguyen: Writing to Re-Member." Helen Scott. Guernica. June 17, 2019.

Notable Literary Births & Events for March 8-14

March 8

Jeffrey Eugenides

Kenneth Grahame

John McPhee

Norman Stone

Douglass Wallop

March 9

Keri Hulme

Vita Sackville-West

Adam Smith publishes The Wealth of Nations (1776)

March 10

David Grann

Janet Mock

John Rechy

March 11

Douglas Adams

Wanda Gág

Ezra Jack Keats

D.J. MacHale

March 12

Sandra Brown

Dave Eggers

Jack Kerouac

Virginia Hamilton

Harry Harrison

March 13

Barry Hughart

W. O. Mitchell

Paul Morand

Viet Thanh Nguyen

David Nobbs

Ellen Raskin

Kemal Tahir

Jean Starr Untermeyer

Hugh Walpole

March 14

Pam Ayres

Paul Guest

Ada Louise Huxtable

Tad Williams