Here are your stories about notable literary birthdays and events for Nov. 18-20.

Nothing humbles me more than when someone decides to pay for my work. Thanks to all who’ve already subscribed to Bidwell Hollow. I’m thrilled to make that commitment worth your while. (And even if you haven’t, you’re still great.)

REMINDER: You can subscribe here for either $5 a month or $50 a year:

Articles like this one will become only for paid subscribers starting Feb. 10, 2020. Subscribe before then to make sure you don’t miss it. Your credit card won’t be charged until Feb. 10. Or, keep your current free subscription, and you’ll continue to get author and poet interviews emailed to you on Tuesdays and book lists on Fridays.

But you won’t receive the weekly rundown of notable literary events and birthdays. Plus, you’ll miss all the other fantastic content I’ll be rolling out.

Nov. 18

Margaret Atwood

When Margaret Atwood first embarked on a writing career, being a woman writer didn’t worry her. Being Canadian did.

“The focus of my young writing career was not ‘I can do this because I’m a woman,’ but ‘this is rather daring for me to be doing as a Canadian’; will I be able to get away with this?’,” Atwood told an interviewer in 1986.

By the time of the interview, Atwood had already published several books, from poetry collections to a few novels. Among her published work was a story that had come out the year prior, in 1985. The book was Atwood’s first bestseller: The Handmaid’s Tale.

Atwood was born on Nov. 18, 1939, in Ottawa, Canada. At that point, Canada had been an independent nation for 71 years. But the country still lacked a vibrant literary industry. The most famous Canadian author during Atwood’s childhood may have been L.M. Montgomery, the author of the children’s book Anne of Green Gables.

And not much had changed by the time Atwood began college at the University of Toronto in the late 1950s. As an undergraduate, Atwood started writing poems. She hung out with other aspiring writers. And while her professors supported her literary ambitions, Atwood didn’t receive much formal writing education.

“The professors were quite good and kind about it at my particular college, and they didn’t laugh openly about what we were writing, but it wasn’t anything like a writing workshop or anything like that,” Atwood said.

So how did Atwood grow into the writer she is today?

“I learned writing by doing it,” she said.

Atwood’s first published work was a poetry collection. Titled Double Persephone, it was a pamphlet that Atwood self-published in 1961. Today, Atwood’s best-known work remains The Handmaid’s Tale. It’s the story of a woman trying to survive in a misogynistic, fascist society called Gilead. The novel’s sold over 8 million copies around the world.

A TV series based on the book recently finished its third season. And in September, Atwood released a follow-up to The Handmaid’s Tale. This book, The Testaments, again focuses on the women of Gilead. The new novel picks up 15 years after the end of its predecessor.

Asked if it was challenging to write a sequel three decades after The Handmaid’s Tale came out, Atwood said no. After all, she started keeping notes about such a project in 1991.

“So then you just jump in and see what happens,” Atwood said.

Nov. 19

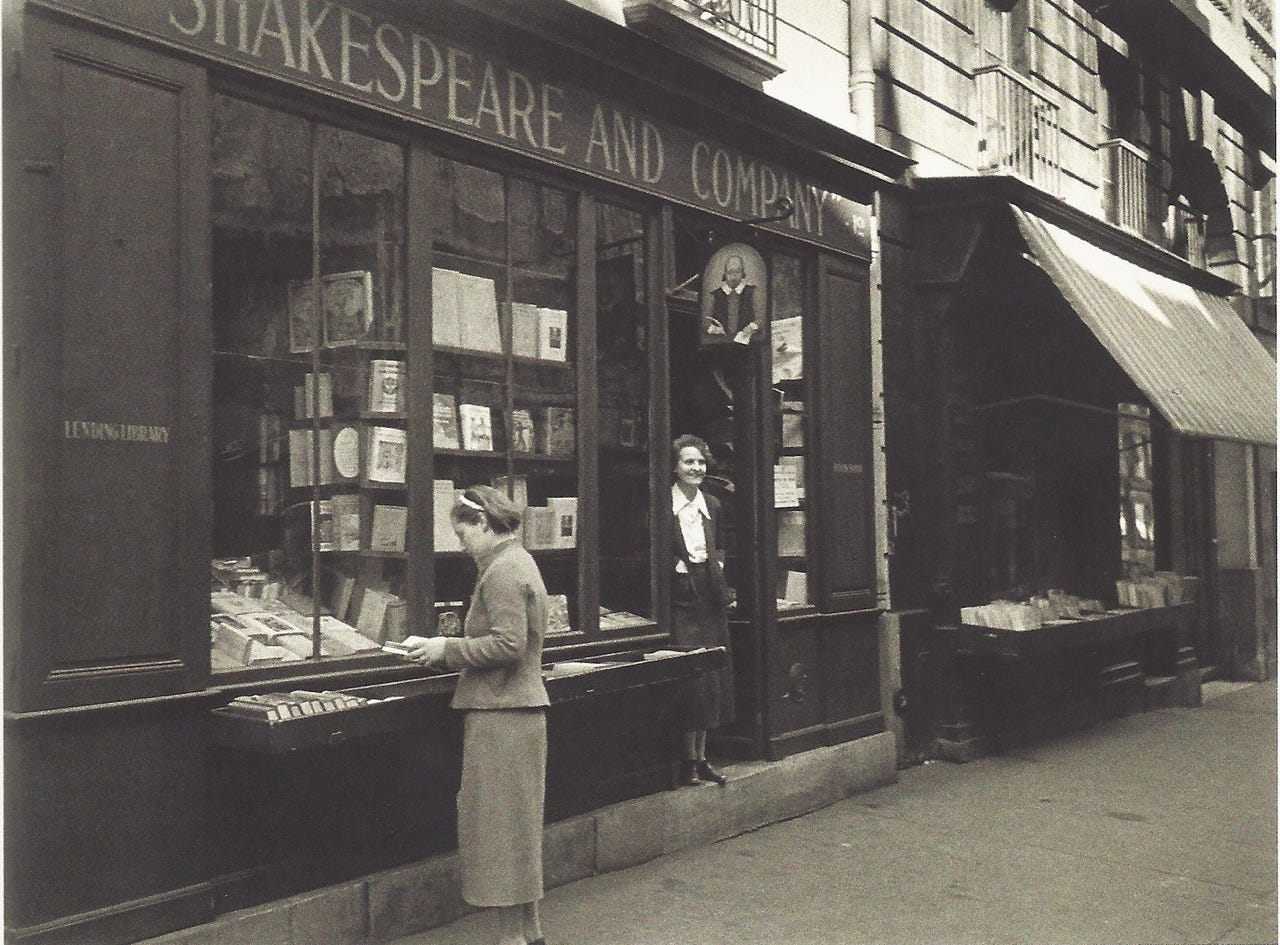

Shakespeare and Company Opens in Paris

One hundred years ago today, in 1919, an American named Sylvia Beach opened a bookstore on Paris’s Left Bank. She called the English bookshop Shakespeare and Company.

The store soon found a customer base in the growing number of English-language readers who were arriving in Paris. Among these folks were writers we now call the Lost Generation: F. Scott Fitzgerald, James Joyce, Gertrude Stein, Djuna Barnes, and Ernest Hemingway.

It was Beach who first published Joyce’s Ulysses in its entirety. The book’s manuscript was too racy for other publishers. And Hemingway had this to say about Beach in his novel A Moveable Feast: “She was kind, cheerful and interested, and loved to make jokes and gossip. No one I knew was ever nicer to me.”

During World War II, as the Nazis invaded France and occupied Paris, Beach stayed with her shop. One day in Dec. 1941, a Nazi officer came into Shakespeare and Company. He wanted to buy a copy of Joyce’s Finnegans Wake. When Beach refused to sell it to him, the officer threatened to return to shut down the store.

So Beach enlisted friends to carry the store’s books to the apartment above the shop where Beach lived. They hid the store’s inventory and then dismantled the store’s bookshelves, too. Still, the Nazis arrested Beach. She spent six months at an internment camp in Vittel, France.

When the Allies liberated Paris in 1944, her old friend, Ernest Hemingway, came to her store to greet her. The famous author declared Shakespeare and Company reopened. But the bookstore never operated again. Beach lived in Paris until her death in 1962.

Today on the Left Bank is another bookstore named Shakespeare and Company. A man named George Whitman opened it in 1951. And this shop, too, has a strong literary history. But that’s a story for another day.

Sharon Olds

Nov. 19 is the birthday of Sharon Olds, a leading poetic voice of her generation. Olds was born in San Francisco in 1942. She grew up in Berkeley, where her parents raised her, as she recalled, a “hellfire Calvinist.”

It’s from her experiences, sex life, and relationships that Olds draws when writing her poems. She’s grouped with Confessional poets such as Sylvia Plath and even Walt Whitman.

“I write the way I perceive, I guess,” Olds said.

Olds’s poems often appear in The New Yorker. And she’s published 12 poetry collections, most recently Arias, which came out in October. For her 1984 book, The Dead and the Living, Olds received the Pulitzer Prize and Britain’s T.S. Eliot Prize. More than 50,000 copies of the book have sold. That success makes The Dead and the Living one of the best-selling contemporary poetry volumes of all time.

Nov. 20

Nadine Gordimer

Nadine Gordimer was born and raised in Springs, South Africa, a mining town not too far from Johannesburg. There, Gordimer benefited from the privileges and prejudices of being white under apartheid.

It’s an experience she wrote about in her autobiographical novel The Lying Days. The book came out in 1953. Gordimer’s hometown is the setting. Throughout the story, the female protagonist awakens to the racism of her upbringing.

The Lying Days is Gordimer’s first novel. Her previous writing had been short stories, which she started penning at age nine. But The Lying Days marked a transition of sorts for Gordimer. From then on, she wrote novels. And her writing focused on the racist policies that governed her country.

Gordimer’s stories showed how apartheid affected her characters’ lives and decisions. For example, an affair between a black man and a white woman are at the center of her novels A World of Strangers and Occasion for Loving. And her 1974 book The Conservationist focuses on a wealthy white South African. The man buys a farm and has to rely on black laborers to manage the property. It’s The Conservationist that brought Gordimer her first taste of international fame. She was a joint Booker Prize winner for the book.

The South African government banned many of Gordimer’s books. The bans didn’t stop until apartheid ended in the early 1990s. Some credit Gordimer’s writing with helping bring an end to that system.

Gordimer received the 1991 Nobel Prize in Literature. She was the first South African writer to win the award and the first woman to do so in 25 years.

Giant Whale Sinks the Essex

On Nov. 20, 1820, a giant sperm whale sank a whaling ship named the Essex. It’s a harrowing tale that gave Herman Melville the ending he sought for his novel Moby-Dick.

The sinking occurred in the South Pacific. There the Essex and its 20-man crew spent a couple of months whaling. Then on Nov. 20, crewman Owen Chase noticed a giant whale in the water with its head pointed toward the Essex. The animal spouted two or three times, then charged the ship. The sperm whale rammed the Essex, disappeared, then reappeared. This time the creature smashed into the bowhead of the boat. The second blow created a hole large enough that water flooded the ship.

The sailors abandoned the Essex by crowding into three rowboats. They drifted at sea for weeks, some resorting to cannibalism to survive. Finally, after months as castaways, passing ships rescued some of the men. Only eight of the 20 crewmembers made it. Chase was among the survivors. He published his account of the sinking of the Essex.

In 1850, Herman Melville was working on his latest book. The story was in part based on the three years he’d spent at sea, including time on a whaling ship. Moby-Dick came out in 1851. In it, a giant whale sinks a vessel called the Pequod. The Pequod’s lone survivor, a sailor, narrates the book. His name is Ishmael.

Sources

I strive to be as accurate as possible in the stories I write. All sources used in researching for Bidwell Hollow’s literary stories are from reputable organizations and authors with trusted fact-checking and editorial processes.

However, errors can occur. If you see a factual error, please let me know. I'll make every effort to verify and correct any factual inaccuracies. Thank you!

Margaret Atwood

“‘I’m Too Old to Be Scared by Much’: Margaret Atwood on Her ‘Handmaid’s Tale’ Sequel.” Alexandra Alter. The New York Times. Sep. 5, 2019. Accessed Sep. 7, 2019.

"Interview with Margaret Atwood." Shannon Hengen and Joyce Meier. Iowa Journal of Literary Studies. Volume 7, Issue 1, Article 3. 1986.

“Full Bibliography” Margaret Atwood.ca. Accessed Sep. 13, 2019.

Shakespeare and Company

“In a Bookstore in Paris.” Bruce Handy. Vanity Fair. Oct. 21, 2014. Accessed Sep. 7, 2019.

“Sylvia Beach.” Elyse Graham. Modernism Lab, Yale University. Undated. Accessed Sep. 7, 2019.

“Sylvia Beach’s Shakespeare and Company, 1919-1941.” Shakespeare and Company. Updated Aug. 2, 2015. Accessed Sep. 7, 2019.

“A Brief History of Shakespeare and Company, Paris’ Legendary Bookstore.” Alex Ledsom. Culture Trip. Feb. 26, 2018. Accessed Sep. 7, 2019.

Sharon Olds

“Benét’s Reader’s Encyclopedia.” HarperCollins Publishers, Inc. Fifth Edition. 2008.

“Sharon Olds.” Poetry Foundation. Undated. Accessed Sep. 7, 2019.

“Biography.” SharonOlds.net. Undated. Accessed Sep. 7, 2019.

"Sharon Olds wins $100,000 Wallace Stevens poetry award." Alison Flood. The Guardian. Sep. 9, 2016. Accessed Sep. 7, 2019.

Nadine Gordimer

“Nadine Gordimer – Facts.” NobelPrize.org. Nobel Media. Undated. Accessed Sep. 7, 2019.

“Benét’s Reader’s Encyclopedia.” HarperCollins Publishers, Inc. Fifth Edition. 2008. Accessed Sep. 7, 2019.

“Nadine Gordimer – Biography.” British Council. Undated. Accessed Sep. 7, 2019.

"Nadine Gordimer." South African History Online. Undated. Accessed Sep. 7, 2019.

“Nadine Gordimer – 1923-2014.” Milton Shain and Miriam Pimstone. Jewish Women’s Archive. Feb. 27, 2009. Accessed Sep. 7, 2019.

The Sinking of the Essex

"The True-Life Horror That Inspired Moby-Dick." Gilbert King. Smithsonian.com. March 1, 2013. Accessed Sep. 7, 2019.

“Nov 20, 1820 CE: Tragedy of the Whaleship Essex.” National Geographic. Undated. Accessed Sep. 7, 2019.

“Whaleship Essex Sinks.” Mass Moments. Undated. Accessed Sep. 7, 2019.

“This Real-Life Whaling Disaster Inspired ‘Moby-Dick’." Xabier Armendáriz. National Geographic History magazine. Nov/Dec 2016. Accessed Sep. 7, 2019.

"Resurrecting The Tale That Inspired and Sank Melville." Mel Gussow. The New York Times. Aug. 1, 2000. Accessed Sep. 7, 2019.

"The Life of Herman Melville." American Experience. PBS. Undated. Accessed Sep. 7, 2019.