Here are your Literary Stories from Bidwell Hollow for Jan. 2-5.

Twice-weekly articles like this one will be available only to paying subscribers starting on Feb. 10. You can subscribe below for either $5/month or $50/year. That’s $50 for 104 stories a year (48 cents per story). Your credit card won’t be charged until Feb. 10. Also, all paid subscribers are eligible to win the monthly book giveaway. Become a paid subscriber before the first drawing on Jan. 22, 2020.

Free editions of Literary Stories left: 9

Jan. 6

Elizabeth Strout

Jan. 6 is the birthday of a writer who taught at a community college for 13 years. Elizabeth Strout started at The Borough of Manhattan Community College in 1983. She got the teaching gig through a woman named Kathy Chamberlain. Strout met Chamberlain at a fiction writing class both women took at the New School.

Chamberlain taught at the College and thought Strout could, too. Strout was a 27-year-old law school graduate who’d been writing most of her life. Plus, magazines such as Redbook and Seventeen started publishing some of her stories.

Strout taught literature and composition. “I loved both, especially literature, because so many of those students didn’t know reading could be fun,” Strout said. “I was young and would come in so enthusiastic about a book that they would sort of sit up and say, ‘Oh.’”

Chamberlain and Strout remained friends. And Chamberlain became the first person to read Strout’s writing, including Strout’s first novel, Amy and Isabelle. The book came out in 1998 when Strout was 42. It’s the first time she’d made any serious money as a writer. She taught at the College for another two years before becoming a full-time novelist.

Strout published Olive Kitteridge in 2008. It’s a collection of 13 stories about a wife and mother of an adult son in a small town in Maine. The book won the 2009 Pulitzer Prize in fiction. And HBO made it into a miniseries starring Oscar-winner Frances McDormand and actor Richard Jenkins.

Since then, Strout’s produced bestselling books such as My Name is Lucy Barton and Olive, Again. Strout doesn’t write her stories linearly. Instead, she composes scenes and later strings them together. “Whatever my emotional hook was that day, I would take that anxiety and transpose it into something the character was doing,” Strout said. “Not the same problem, but the same anxiety. That way, there would be a heartbeat to the scene or a better chance of it.”

Strout was born in Portland, Maine, in 1956. She’s the author of seven books.

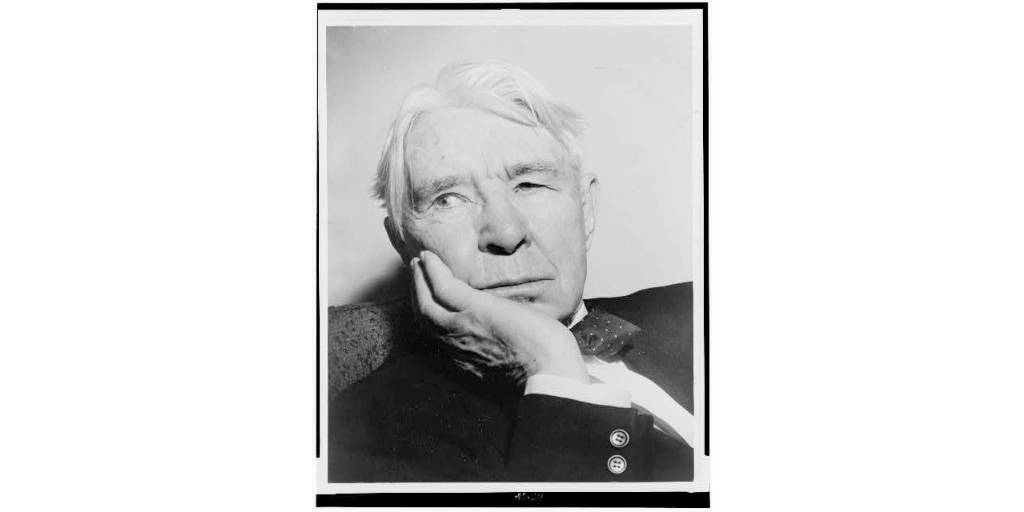

Carl Sandburg

On Feb. 12, 1959, a joint session of Congress convened. It was the 150th anniversary of President Abraham Lincoln’s birth. Speaker of the House Sam Rayburn introduced the day’s marquee speaker.

“And now it becomes my great pleasure, and I deem it a high privilege, to be able to present to you the man who in all probability knows more about the life, the times, the hopes, and the aspirations of Abraham Lincoln than any other human being,” Rayburn said. “He has studied and has put on paper his conceptions of the towering figure of this great and this good man. I take pleasure, and I deem it an honor to be able to present to you this great writer, this great historian, Carl Sandburg.”

Members of Congress rose and applauded the three-time Pulitzer Prize winner. And then Sandburg began. “Not often in the story of mankind does a man arrive on earth who is both steel and velvet, who is as hard as rock and soft as drifting fog, who holds in his heart and mind the paradox of terrible storm and peace unspeakable and perfect. Here and there across centuries come reports of men alleged to have these contrasts. And the incomparable Abraham Lincoln born 150 years ago this day, is an approach if not a perfect realization of this character.”

Sandburg spoke that day because he’d written a six-volume biography of Lincoln. The first two volumes, Abraham Lincoln: The Prairie Years, came out in 1926. Then the writer spent 13 years working on the next set of books. In his first year of research, he read 1,000 books. He poured over archives from newspapers published in the North and South during the Civil War. And he met with historians, librarians, and descendants of those who lived during Lincoln’s time.

The result was the four-volume Abraham Lincoln: The War Years. It came out in 1939. For the biography, Sandburg won the 1940 Pulitzer Prize in history. And it cemented his reputation as an expert on America’s 16th President.

Sandburg was born on Jan. 6, 1878, in a three-room cottage in Galesburg, Ill. His birth was 20 years after the town hosted a debate between then-U.S. Senate candidate Lincoln and Stephen A. Douglas. Growing up, Sandburg heard stories from people who’d been at the debate and some who’d known Lincoln. The experience instilled in Sandburg a lifelong fascination with Lincoln.

Along with writing about Lincoln, Sandburg made a name for himself as a poet. He earned his first Pulitzer Prize for his poetry collection, Corn Huskers, in 1919. And he added a second Pulitzer in poetry for his 1950 volume Complete Poems.

Today on the Public Square in his native Galesburg, you’ll find a nine-foot-tall bronze statue of Sandburg and his goat, Nellie. A goat may seem like an odd choice. But for three decades, Sandburg’s wife, Lilian, ran a 245-acre goat farm at Connemara in Flat Rock, N.C. It’s there that Carl Sandburg passed away on July 22, 1967.

Jan. 7

Zora Neale Hurston

On Jan. 25, thousands of people will converge on Eatonville, Fla. They’ll come to discuss black American culture and economic issues and to have some fun. And throughout the event, they’ll celebrate Eatonville’s famous daughter, Zora Neale Hurston.

The Zora! Festival started in 1990. At the time, Orange County leaders wanted to build a five-lane highway through Eatonville’s historic downtown. Former slaves founded Eatonville. The town became the first all-black community to incorporate in the U.S. in Aug. 1887.

Hurston claimed she was born there, but that wasn’t true. She was born on Jan. 7, 1891, in Notasulga, Ala. Her family moved to Eatonville when she was a toddler, though. And she grew up there before arriving in New York during the Harlem Renaissance in the 1920s.

Hurston earned degrees from Howard University and Barnard College. She befriended Langston Hughes and wrote plays and novels. Among her books is Their Eyes Were Watching God, which came out in 1937. And Hurston studied black Southern culture, using much of what she learned in her writing.

She published in 1935 a book about black traditions. In that book, Mules and Men, Hurston described Eatonville as “the city of five lakes, three croquet courts, 300 brown skins, 300 good swimmers, plenty guavas, two schools, and no jailhouse.”

But most people forgot about Zora Neale Hurston by the time she died in 1960, including some of the folks in Eatonville. The last book she published came out in 1948. She passed away in a nursing home in Fort Pierce, Fla., and was buried in an unmarked grave.

Then Alice Walker wrote an article for Ms. magazine in 1975 that highlighted Hurston’s work. The piece, “In Search of Zora Neale Hurston,” ignited interest in Hurston. People started reading the later writer’s books. By the late 1980s, many high school teachers and college professors added Their Eyes Were Watching God to their courses’ reading lists.

So when officials planned to run a highway through Hurston’s hometown, Eatonville leaders took action. They formed the Zora! Festival to highlight both the writer’s work and the city’s history. Their goal was to show county leaders what would be lost if they proceeded with their plan to build the roadway.

And it worked. After a few years, Orange County gave up trying to build a five-lane road through Eatonville. And much of Eatonville’s downtown joined the National Register of Historic Places in 1998.

To date, more than 1.5 million people have attended the Zora! Festival. This year’s event, the 31st annual, runs from Jan. 25-Feb. 2.

Sources

Significant effort goes into ensuring the information shared in Bidwell Hollow’s Literary Stories is factual and accurate. However, errors can occur. If you see a factual error, please let me know by emailing nick@bidwellhollow.com. I'll make every effort to verify and correct any factual inaccuracies. Thank you.

Elizabeth Strout

"About Elizabeth.” ElizabethStrout.com. Accessed on Jan. 4, 2020.

"Elizabeth Strout: 'Nobody was even remotely interested in my writing'." Alice Jones. i Newspaper. June 5, 2018. Updated on Sep. 6, 2019. Accessed on Jan. 4, 2020.

"How Elizabeth Strout Paid the Bills While She Wrote the Books." Mike Gardner. Medium. Feb. 19, 2019. Accessed on Jan. 4, 2020.

"Elizabeth Strout's Long Home Coming." Ariel Levy. The New Yorker. April 24, 2017. Accessed on Jan. 4, 2020.

"Writing: A Lifelong Study of the Human Condition." Borough of Manhattan Community College. Jan. 4, 2010. Accessed on Jan. 5, 2020.

"The Best Lingerie Shop in NYC, According to a Pulitzer Prize-Winning Author." Barbara Hoffman. New York Post. May 4, 2018. Accessed on Jan. 5, 2020.

Carl Sandburg

"Carl Sandburg Biography and Timeline." Dr. Penelope Niven. PBS. Aug. 18, 2012. Accessed on Jan. 4, 2020.

"Address of Carl Sandburg Before a Joint Session of Congress, February 12, 1959." The University of Southern Mississippi. Accessed on Jan. 4, 2020.

"Full Text of 'Abraham Lincoln Volume 1 The Prairie Years Carl Sandburg'." Internet Archive. Accessed on Jan. 4, 2020.

"Sandburg's Lincoln." National Park Service. Accessed on Jan. 4, 2020.

"A Workingman's Poet." Danny Heitman. Humanities. March/April 2013. Accessed on Jan. 4, 2020.

"Public Art Commission Dedicates Sandburg Statue to City." Tom Loewy. The Register-Mail. April 30, 2016. Accessed on Jan. 4, 2020.

"Goats Rule at Newly Renovated Carl Sandburg Home in Flat Rock, N.C." Sylvia Wrobel. Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Oct. 12, 2018. Accessed on Jan. 4, 2020.

Zora Neale Hurston

"Dust Tracks on a Road: An Autobiography." Zora Neale Hurston. Harper Collins. July 13, 2010.

"Zora Neale Hurston." The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. Encyclopaedia Britannica. Jan. 3, 2020. Accessed on Jan. 5, 2020.

"In a Town Apart, the Pride and Trials of Black Life." Damien Cave. The New York Times. Sep. 28, 2008. Accessed on Jan. 5, 2020.

"Is Eatonville History Vanishing?" Christopher Sherman. The Orlando Sentinel. Oct. 3, 2005. Accessed on Jan. 5, 2020.

"About Zora Neale Hurston." Zora! Festival. Accessed on Jan. 5, 2020.

"A Society of One." Claudia Roth Pierpont. The New Yorker. Feb. 9, 1997. Accessed on Jan. 5, 2020.

"The Coming of a Town." Eatonville History. Accessed on Jan. 5, 2020.

"Recovering Zora Neale Hurston's Work." Dorothy Abbott. Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies. Vol. 12, No. 1, 1991.